By Robert H.

So I am going to start this boringly and at a high level of abstraction, but I think laying the groundwork is important:

Empathy is when you know all too well what someone is going through, can put yourself in their situation, and you actually sort of feel their pain.

Sympathy is when you can't put yourself in someone's shoes or really understand what they are going through, but you still feel bad for their pain.

An interesting distinction between the two is that you can't really have mixed emotions about the subject of your empathy (if I am feeling what you are feeling, I can't be also feeling that, say, I hate you, because you aren't feeling that), but mixed emotions are possible (and common?) with sympathy. I can feel bad for your suffering but also be sort of glad it is happening and also be confused about the contradiction and also want you to get over it and stop whining.

I bring all this up because I was always raised to believe that sympathy is never wrong. If someone says, "I'm glad he's dead, and I wouldn't have preferred a different outcome, but I still sort of feel bad for Hitler, dying alone and beaten in a bunker," I would think, "Ok. That's pretty damned charitable, and I don't feel that way, but good for you." Being able to see the humanity in monstrous people isn't bad, it's the sign of a saint.

The problem, I was always taught, is when you either 1. Let your sympathy get the better of your judgment, and go from feeling bad for someone to excusing them from the consequences of their actions; or 2. Actually start empathizing with bad people. If someone says "I feel bad for Hitler, I wish he had escaped to Argentina" or, even more creepily, "I totally feel Hitler's pain. His noble attempts to conquer Europe overthrown, the evil Allies closing in on him, forced to take his own life..." then that's disgusting and wrong.

I bring all this up because there has been a lot of weird (if predictable) empathizing/taking-sympathy-too-far with the two kids recently convicted of raping their classmate in Steubenville.

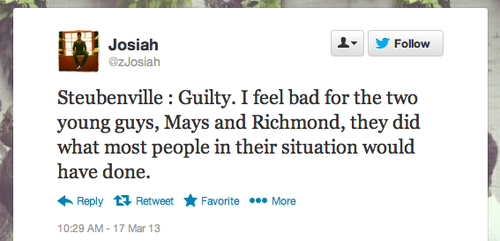

Here's a tumblr that is collecting some examples (plus examples of people attacking the victim). Terrifying stuff like:

That is clearly someone who empathizes with rapists, and that's terrible.

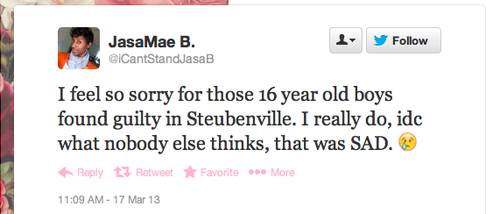

But in the rush to go after people like that, I've seen people simply expressing sympathy for the rapists being swept up in the same pile of dust. That same tumblr, for example, contains this entry:

Now that certainly wasn't my reaction, and I think there's a good chance that that dude, if you pressed him, would reveal that he's fallen into one of the two errors I talked about above. But I don't see absolute proof of that in the tweet as written. Some young kids are going to jail and this dude feels bad for them and thinks it is sad. We don't know if he thinks the verdict is wrong, or if he blames the victim, or if he is imagining himself in the boys' shoes, or if he is feeling other emotions, we just know he feels sympathy for bad humans experiencing something bad. Let him! Sympathy is fine!

As a less borderline example, CNN's coverage of the sentencing

has come under fire. Part of the criticism is just wrong (that writer goes after CNN for focusing on the rapists but leaving the victim a nonentity, but she is only looking at a snippet of the broadcast.

Later in the broadcast, and seemingly as soon as possible, they did, in fact, seek out a representative for the victim (her attorney), inquire after how she was doing, and give him a chance to speak on her behalf. They also reported on the victim's mother's reaction to the sentencing), part of the criticism is absolutely right (that writer missed it, but CNN broadcast the victim's name, which is inexcusable), but some of it falls prey to this sympathy/empathy thing. People hear CNN reporters expressing sympathy for the rapists and talking about what a shitty turn their lives will now take and assume that they are either excusing them or empathizing with them or trying to make the viewer like the rapists more or implying that everyone should feel the way the cnn reporters do. Maybe I'm tone deaf, but I didn't hear any indication of that, I just heard sympathy. I think the reporters were just expressing what they felt they just watched some sad people getting their life destroyed and feel kind of bad for them. That's not the worst way to feel. Had the reporters only expressed that sympathy, and not counterposed it with the heinousness of the crime and the suffering of the victim (which they didn't do enough of, I admit, in the clip that writer is spotlighting. But again, that clip was not the whole broadcast), I think you could fairly criticize them. And even as is I think you could say, "man, that's not how I would have reacted to or reported that trial." But saying, "No sympathy on the TV for violent criminals! Ever!" strikes me as a bit much. Feeling sympathy for bad people is fine!

As a caveat, I admit I might be mixed up about this "sympathy is never wrong" axiom.

And just to clarify: yes, obviously I am glad that the two rapists are going to jail, and no, I don't feel much sympathy for them. I do feel bad for the rapists' families, though, and I also think my feelings might be different if I had been at the sentencing hearing (I think I would both feel both more sympathy and even more hatred and disgust for the criminals. Sentencing hearings are emotional, yo).

Lastly, I just want to emphasize that "idiots blaming the victim or excusing the criminals" has been a much bigger, more noticeable, and badder problem in the aftermath of this trial than "excessive policing of sympathy" has been. Rape culture is a million times worse than is people over-zealously attacking examples of rape culture. I'm writing about the second thing because I haven't seen anyone make the point I want to make (a good sign I'm wrong?), not because it's more important than the first thing.

P.S. I won't be able to update tomorrow. Apologies.

.jpg)